by Jenni Carlson, The Oklahoman/NewsOK.com

Watching his adopted hometown of Baltimore’s downward spiral into violence and rioting and chaos saddened Joe Ehrmann.

It didn’t surprise him.

Ehrmann also saw problems there.

“Apathy,” he said. “Generations of that indifference.”

That Ehrmann was in Oklahoma City on Monday is hope that we might avoid some of those same problems.

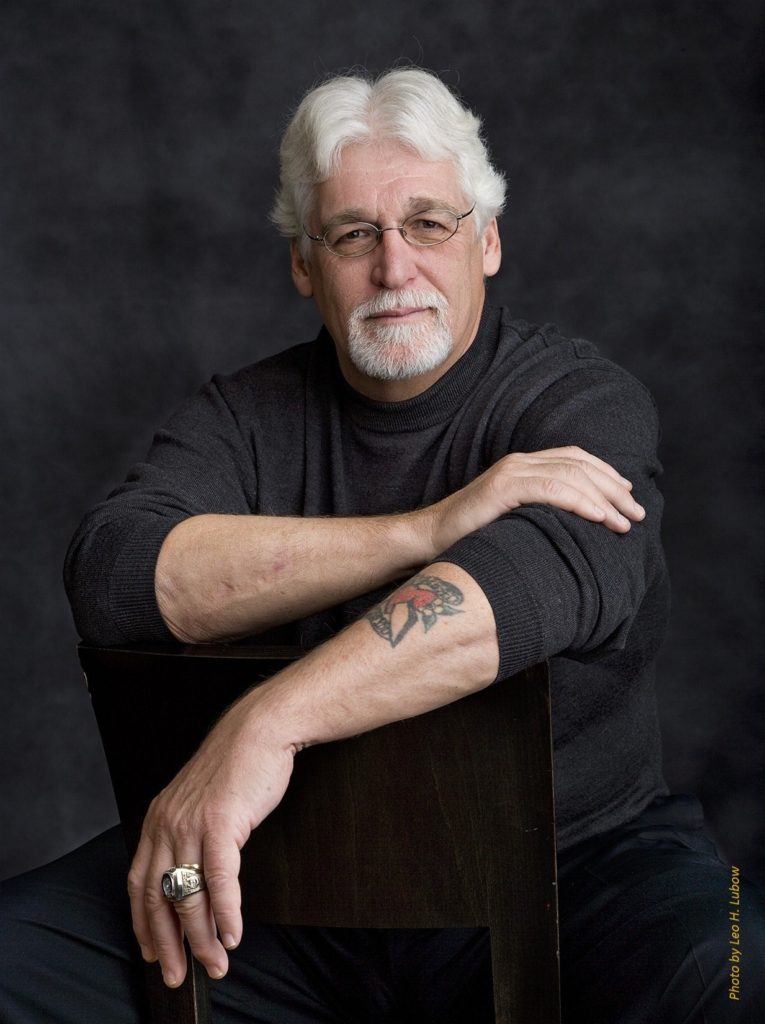

The man who has been called “The Most Important Coach in America” came to town for Oklahoma City Public School’s Athletics Spring Awards Banquet. His message was one that he preaches all over the country — sports can transform lives but only with transformational coaches — and he was brought in by Fields & Futures and the Wes Welker Foundation and a bunch of folks who want to make things better in Oklahoma City.

Apathetic, they are not.

Neither is Ehrmann.

He played his last pro football game in 1985. He spent a couple years with the Detroit Lions after leaving the Colts, then played three seasons in the upstart USFL. But when he retired after more than a decade as a pro, he expected to never step on a field again.

“I was done with sports,” he said.

Sports had long been part of his life, but as he got older, he had realized it defined him. He’d been told to “be a man” when he was young, then he’d been socialized to believe that being a great athlete was a sign of his toughness, his masculinity, his manhood.

He realized that was bunk.

So, Ehrmann dove into theology, attended seminary and became ordained the same year he retired from football. He and his wife, Paula, started a community center in inner-city Baltimore called “The Door” and began ministering to people who desperately needed help and hope.

It wasn’t long before Ehrmann found himself back on a football field.

Why?

A team of inner-city 8 year olds needed a coach.

Turns out, that team changed Ehrmann’s life. Being around those kids, he quickly realized that sports was one of the greatest tools for the societal change that he so wanted to bring. Sports touches millions of kids every year, and through sports, they could be taught that being a real man emanates from the heart. Emotions build connections to others, which leads to compassion and caring and empathy.

A lack of empathy, Ehrmann believes, leads eventually to bullying and violence.

Ehrmann began to develop a curriculum for coaches. A plan for teaching important values. A process for educating the coaches.

In doing that, he realized that there are two types of coaches — transactional and transformational.

“The transactional coaches … it’s about them, their identity,” Ehrmann said. “It’s always coach first, win-loss record and then players’ needs somewhere down the road.

“Transformational coaches understand the position they have in the lives of young people, and they’re going to use it to change the arc of every young person’s life. They mentor.”

He thought about every coach he had in his life, dozens of them over nearly three decades in football and lacrosse and other sports. Only three of those coaches were of the transformational variety.

Not a high number.

“But all a boy needs really is one,” Ehrmann said.

It wasn’t long before he decided that he needed to keep coaching. Maybe he could spread his ideology. Perhaps he could coach the coaches.

He began coaching at Gilman School, an urban private school in Baltimore, and his philosophy took off. He taught all the coaches there. He mentored coaches at other schools in and around Baltimore.

Eventually, word began to spread outside the schools about what he was doing. Jeffrey Marx, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who was a Colts’ ball boy once upon a time, heard about it and decided he wanted to write a book about Ehrmann in 2004.

“Season of Life” became a national bestseller and is now in its 36th printing.

A few years ago, Ehrmann wrote his own book, “InSideOut Coaching,” which has drawn praise from near (Joe Castiglione) and far (Tony Dungy).

And lest you think Ehrmann’s philosophy leads to non-competitive teams, nothing could be further from the truth.

“Our goal is always to win,” he said. “Our purpose is to transform lives.”

In the decade since “Season of Life” came out, Ehrmann has been all over the country spreading his gospel. He patterns it after what he’s done in Baltimore. Coaches there talk during the first half of the season about becoming an involved man and fostering emotions such as empathy. In the second half of the season, they focus on different societal issues such as poverty, abuse, violence and race.

Baltimore schools are more than 90 percent black, and yet, Ehrmann is always surprised during “race week” how few of the kids have any knowledge of the civil rights movement.

Players learn about Dred Scott, the slave whose fight for his freedom went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. They have conversations about assumptions that they have based on someone’s skin color. They memorize the Langston Hughes poem “I, Too, Sing America.”

As Ehrmann talked about those lessons Monday, he began to recite the poem.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed —

I, too, am America.

But even as Ehrmann has tried to change the culture in Baltimore, he wasn’t surprised to see the violence that erupted there several weeks ago. The death of Freddie Gray brought out festering problems. Lacking jobs. Poor schools.

The dropout rate in inner-city Baltimore is 65 percent, which leads to poverty and hopelessness and anger.

Reducing the dropout rate is one of the reasons that a conglomerate is trying to transform sports in Oklahoma City Public Schools. Fields & Futures is renovating facilities. The Wes Welker Foundation is funding equipment. Cleats for Kids is providing gear. And spearheaded by Oklahoma City Public athletic director Keith Sinor, the district is attempting to rethink the way sports are done.

This past year, every team in the district instituted a character program that recognized athletes for everything from teamwork to effort.

Monday, Sinor and his helpers brought in Ehrmann to lay a little more track for their train.

“It’s a part of the solution,” Ehrmann said what’s happening here. “It’s a sign of hope.

“Those fields become sacred places, holy places. You’re transforming lives on those fields.”

Consider that a big pat on the back for Oklahoma City. America’s coach likes what he sees in this team.

Jenni Carlson can be reached at (405) 475-4125 or [email protected]. Like her at facebook.com/JenniCarlsonOK, follow her at twitter.com/jennicarlson_ok or view her personality page at newsok.com/jennicarlson.